Heading to the Hall

The standard bearer for Illinois Wesleyan basketball, Jack Sikma ’77 will be immortalized as an inductee into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in September 2019.

Story by Matt Wing

Jack Sikma ’77 squirmed in the oversized chair in the study of his suburban Seattle home, knowing his phone would soon ring.

The call was coming either way. Good or bad.

The former Illinois Wesleyan basketball star, who went on to a 14-year career in the National Basketball Association, had learned he was a finalist for the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame a couple months earlier.

But it was on this day he’d learn if he was joining the elite fraternity.

“I was nervous,” Sikma admitted.

But he didn’t need to be. The call came. The news was good.

“There wasn’t any jumping up and down or anything,” he recalled. “I kind of went to a quiet place and just thought about the journey, and I kind of found my mind wandering to different snapshots of my life. I just sat there quiet for a while.

“It almost started to overwhelm me a bit, the thoughts and all the people who came to mind.”

When he is inducted on Sept. 6, 2019, in Springfield, Massachusetts, Sikma will officially join the ranks of the game’s all-time greatest players, and he’ll do so as one of just a handful of American players having played their college basketball outside of Division I.

Sikma’s basketball odyssey took him from his tiny hometown of Wichert, Illinois, to nearby St. Anne High School, and eventually to Illinois Wesleyan.

The journey continued when he was drafted by the Seattle SuperSonics, for whom he played for nine seasons before finishing his playing career with the Milwaukee Bucks. He later coached for Seattle, the Houston Rockets and Minnesota Timberwolves, and is currently a part-time consultant for the Toronto Raptors, who won the 2019 NBA championship.

Sikma says he is lucky to have had mentors and friends at each stop along the way. He plans to retrace his steps in a pilgrimage of sorts leading up to his induction. And Illinois Wesleyan will be an important stop on the tour.

“I’m going to have fun with this,” Sikma said. “I’m going to see a lot of people, we’re going to share a lot of stories, and I’m really looking forward to it.”

•••

Illinois Wesleyan men’s basketball coach Dennie Bridges ’61 got his first glimpse of the player that would forever change his program on Dec. 30, 1972.

Upon learning from the IWU admissions office there was a 6-foot-9 basketball player ranked third in a class of 117 students at St. Anne High, Bridges sent the player a handwritten letter. The player replied and enclosed a St. Anne basketball schedule, per the coach’s request. Bridges circled Dec. 30 on his calendar.

That night, the Titan coach made the hour drive to Chatsworth, Illinois, to see Jack Sikma playing in the championship game of the holiday tournament there. Sikma was as tall — and as skinny — as advertised. His shooting style was unorthodox, though he made most of his shots.

But what stood out most was something that couldn’t be gleaned from the box score in the next day’s newspaper.

“He was a late bloomer and a tall, skinny kid who could shoot, but what I saw beyond that was what a tremendous competitor he was,” Bridges remembers.

Late in the game, with St. Anne leading by a point and an opposing player at the free-throw line, Bridges observed Sikma snapping his fingers and mouthing “miss it, miss it” as if putting a hex on the player at the charity stripe.

Bridges was sold. The coach’s enthusiasm was tempered, however, by the reality that Sikma could be poached by a bigger school offering a grander stage and a full athletic scholarship. And as Sikma piled up the points and rebounds, and St. Anne High kept winning, that’s exactly what happened. When St. Anne qualified for the state tournament, blue bloods like Illinois, Purdue and Kansas State entered the picture.

Nevertheless, Bridges remained dogged in his pursuit of Sikma. He convinced the shaggy-haired 17-year-old to visit campus, where he was hosted by a group from Sigma Chi, a fraternity he later joined. Bridges continually stressed to Sikma that he’d get a complete college experience at IWU — including ample opportunities to have fun — whereas his life at a Division I school would be much more basketball-centric. “The biggest thing I did was contrast the kind of life it was going to be,” Bridges explained.

Sikma eventually committed to IWU, even as the University of Illinois ratcheted up its recruitment. And with no athletic scholarship or letter of intent, the Illini staff continued to woo Sikma even after he announced his commitment to IWU.

Bridges found every excuse to make daily contact with Sikma. If he didn’t call, he wrote a letter. They met for golf. They went to a Chicago White Sox game.

“I trusted him, and I trusted his family,” Bridges said. “But Illinois wasn’t letting up and until the day he came in and enrolled, I was worried about it.”

But he didn’t need to worry. Sikma showed up for his first day of class.

And he stuck around for four very memorable years.

“I made the decision to come to Illinois Wesleyan and it was the best decision I could’ve made, looking back,” Sikma said.

•••

In 36 years as IWU’s head basketball coach, Bridges never promised a player a starting job … with one notable exception.

Sikma was on the floor for the opening tip of Illinois Wesleyan’s 1973-74 season opener. He immediately became a key contributor, at times combining his size with a deft shooting touch to become a serious dual threat. Other times, his aggressive play backfired and he found himself on the bench saddled with foul trouble.

“I remember a game at Millikin and I had a pretty bad first half,” Sikma recalled. “We got in the locker room and Coach came right up and got on me about not focusing and not playing smart, but that was the kind of relationship we had.

“I needed those challenges to perform at a high level.”

Sikma showed right away he could be a difference maker for Illinois Wesleyan, but Bridges knew his big man could do more. He toyed with the idea of helping Sikma develop a “go-to” move. The two experimented with a variety of post moves with varying levels of success.

They eventually tried the inside pivot, a move Bridges remembers being deployed primarily by “big clods” who lacked speed and agility. The inside pivot required a player to accept a post-entry pass with their back to the basket before swinging a pivot foot around to face the basket and create separation from the defender. The player then had two choices: shoot the ball from the newly created space, or put the ball on the floor and drive to the basket if the defender tried to close too quickly.

Of almost equal importance was an emphasis on releasing his shot from higher above his head to prevent blocked shots.

Sikma spent countless hours the summer between his freshman and sophomore years refining the maneuver.

“We did repetitions from both sides, moving with both feet, and I started to become more comfortable with it,” he said. “But I do remember sophomore year, at first, I wouldn’t automatically go to it. It hadn’t set in yet.”

Sikma would occasionally revert to a reliance on his size and physicality — which still worked most of the time — at which point Bridges would offer not-so-subtle reminders about the game plan.

“I’d say, ‘Damn it, Jack! Where’s your move?’” Bridges remembers, reenacting the familiar exchange with a wave of his arms. The coach smiles while telling the story, though he certainly wasn’t smiling back then.

But with enough coaxing and countless repetitions, “the move” became second nature. Sikma remembers a game at Elmhurst during his sophomore year when he scored nearly 20 points in the first half, most the result of “the move.”

It finally clicked.

“From there, I saw that it could be very successful, so I built the basis for my post game off of it,” Sikma said. “Coach Bridges taught me the move and I worked to perfect it.”

Sikma became a three-time National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) All-American and three-time conference player of the year. He led the Titans to conference titles and NAIA Tournament appearances in each of those final three seasons (Illinois Wesleyan joined NCAA Division III a few years later).

Playing in the national tournament afforded Sikma an opportunity to showcase his skills against the best teams in the country. So did frequent games against Division I opponents. But perhaps the best proving ground came when he was invited to the 1976 U.S. Olympic trials.

Sikma entered the tryout for the national team as an afterthought in the eyes of some — “probably the 10th- or 11th-rated center at the start,” Bridges states — but was a controversial omission at the final cut after proving himself against some of the top players in the country. Sikma finished his IWU career with school records for points (2,272) and rebounds (1,405) that stand to this day. His No. 44 remains the only number to be retired by the team. He developed a maneuver that would later become known by many as the “Sikma move.” And he put himself on the radar of professional teams.

At 6-foot-11 by his senior year, Sikma stood out beyond his achievements on the basketball court. He was active in Sigma Chi. He excelled in the classroom and twice earned Academic All-America status. He remains Illinois Wesleyan’s lone selection to the Academic All-America Hall of Fame.

“I made some great friends, had a lot of fun, did well academically. I was able to improve as a basketball player, and that opened up possibilities in that regard,” Sikma said. “Illinois Wesleyan was exactly what I was looking for and it was absolutely the right place for me.”

•••

The headline of one Seattle newspaper on the morning of June 11, 1977, poked fun at the player the hometown SuperSonics had picked with the eighth overall selection in the NBA Draft.

“Jack who?” it read, questioning the legitimacy of a player from a small private school playing at the NAIA level.

“A sports writer from out there called and said the people out there weren’t too happy,” Bridges recalls, smiling again. “I told him to call me back in a year.”

Sikma was named to the NBA’s All-Rookie team and helped the Sonics to the NBA Finals in his first season. The next year, he was named to his first of seven-straight All-Star games and led Seattle to its first and only NBA championship.

Bridges can’t remember if that sports writer ever called back.

“The greatest thing about Jack’s career is he just continued to get better,” the longtime IWU coach said. “At our place, he grew and got stronger, learned his move and got things started.

But then as he went to the NBA, he continued to get better.”

Sikma averaged a double-double (with double-digit points and rebounds) for seven-straight seasons. He thrived in the NBA’s meritocracy that cared only for what you could do on that given night.

“I was going to find a way to get out on that court,” Sikma said. “That’s the great thing about the NBA: it’s not what you’ve done in the past but what you’re doing now.”

Sikma continued to improve as his NBA career progressed, and he found new ways to contribute. He became one of the best passing centers in the game. In 1987-88, he led the NBA in free-throw percentage, and is still the only individual playing primarily at center to ever do so. As his career wound down, he extended his shooting range and became one of the first sharpshooting big men.

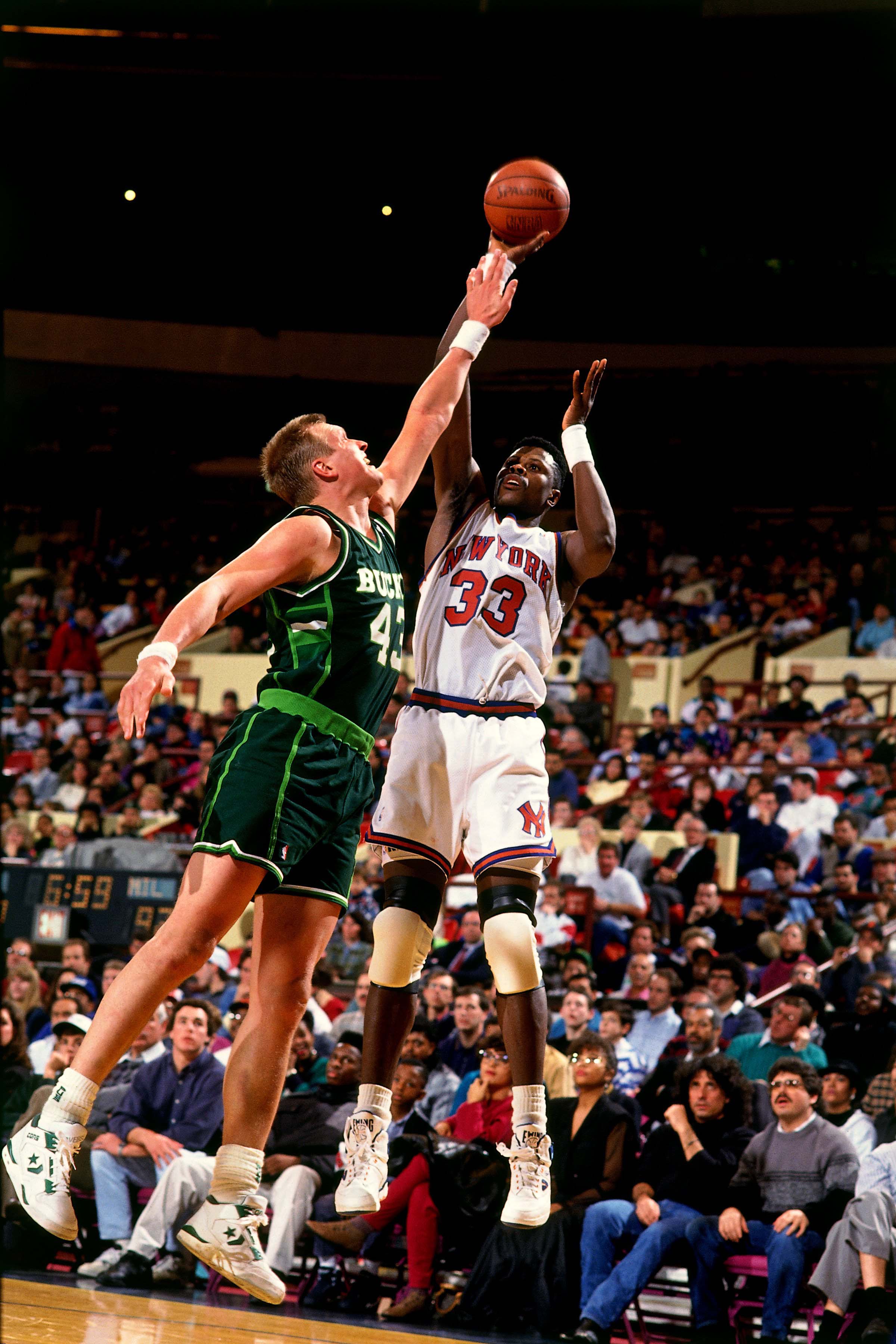

And he did it all during a golden age of NBA post players. The IWU alum had his best seasons going up against the likes of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Moses Malone, Hakeem Olajuwon and Patrick Ewing — all fellow Hall of Famers — on a nightly basis.

“I never really focused on who I was playing. It was more about what I needed to do,” Sikma said. “But when you think of all the winners I had to square off with and how many of them are in the Hall of Fame, I feel even better about what I accomplished out there because I competed against the best.”

•••

When Sikma retired after the 1990-91 season, most of today’s NBA players hadn’t even been born yet.

But his influence on future generations is undeniable.

“Even today, you’ll be watching a game and someone will use his move and the announcer will say, ‘Somewhere Jack Sikma is smiling,’” Bridges explains.

Through his role as an NBA assistant coach, he’s directly influenced today’s players. He’s mentored All-NBA selections Yao Ming, Dikembe Mutombo, Kevin Love and, most recently, Marc Gasol.

“I’ve really liked working with young players who are discovering their talents and what they can be,” Sikma said. “Helping them to try to raise the ceiling they can get to has been a lot of fun and very rewarding.”

Sikma continued to influence IWU basketball, too, years after his last game as a Titan.

“Every year I would pick out three or four kids who I really wanted and I kind of wrote a letter for Jack that he could copy and sign and send to these kids,” Bridges said. “But it got to be that the players were comparing who got a Sikma letter and who didn’t, and if you didn’t get a Sikma letter, Coach Bridges must not have thought you were very good.”

Sikma also impacted hundreds of young players from the Bloomington-Normal community when he co-hosted a summer basketball camp at IWU for many years with Bridges.

And one of those inspired kids just happened to be one of Bridges’ sons.

“The camp gave us a reason every summer to play golf and have fun, and every year we’d have a party over at my house with all the coaches and their wives,” Bridges said. “We were on the back porch one night and I looked out in the driveway and there was Jack, playing 1-on-1 with my son.

“And that’s just the kind of guy Jack is.”

•••

Sikma’s Hall of Fame induction is still a few months away, but his basketball pilgrimage is well underway.

It started in April at the Final Four in Minneapolis when the announcement was made. There, he was joined by Bridges and a few former IWU classmates who helped celebrate. And with a virtual Who’s Who of basketball lifers in Minneapolis for college basketball’s signature event, Sikma was able to celebrate with many of his NBA peers. Bill Walton, a Hall of Famer Sikma often squared off against early in his career, offered congratulations and told Sikma the honor was “long overdue.” The next night, Charles Barkley pulled up a chair and joined Sikma’s group to celebrate.

The celebration tour continues this summer. Sikma spoke at a YMCA fundraiser in Bloomington, Illinois, in June, giving him an excuse to meet with old friends and his former coach. A few days later, he threw out a ceremonial first pitch at a Chicago Cubs game. On July 21, he’ll take part in a Titan Connection event in Seattle, celebrating his Hall of Fame induction.

Sikma’s only regret in all of it is that his parents won’t be around to see his Hall of Fame induction. But he will be joined by his family — wife, Shawn, and sons Jacob, Lucas and Nathan — and a slew of friends and former teammates, many of them from Illinois Wesleyan.

“The most emotional part of the speech will be about my parents. They were my biggest supporters and invested so much time,” Sikma said. “After I get through that, I want to recognize different times of my life and the people that have been important, and just how fortunate I am.

“Hopefully, I can translate my feelings and appreciation for all those involved and really enjoy the honor of being recognized by my peers and being worthy of the Hall.”